As befits the obsession of today’s scientific circles in the West with language, the specter of the Balkans that does not escape from it is not a person but a name, a signifier. It is predictable that the signifier “Balkan” will separate from its original signified and all subsequent signifiers with which it enters a relationship. In fact, another process was taking place in parallel: while “Balkan” began to be accepted and widely used as a signifier in a geographical sense, it was slowly already beginning to acquire a social and cultural meaning that extended its signified beyond its immediate and concrete meaning. While the “Balkan” encompassed a complex historical phenomenon and began to signify it, some political aspects of this new signified were extrapolated and independently signified.

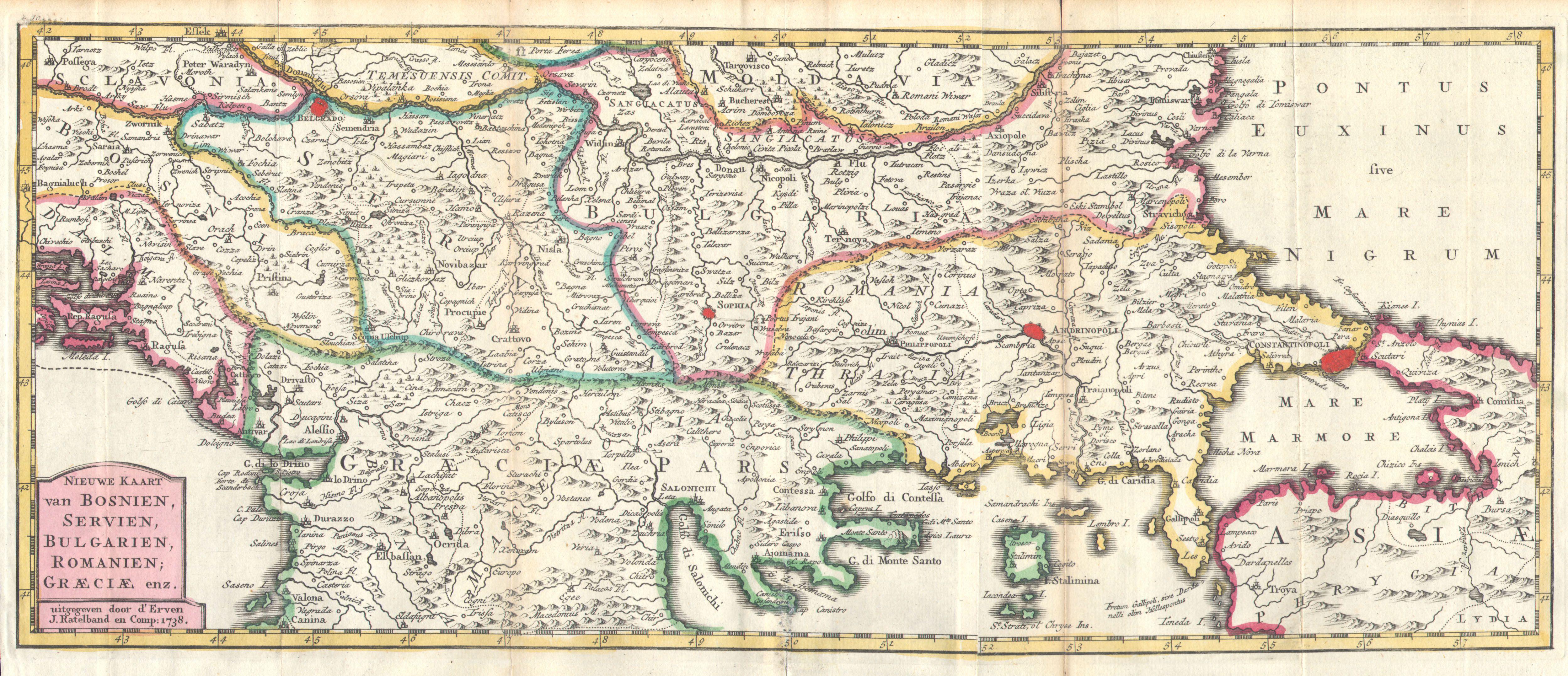

1738 Ratelband Map of the Balkans ( Bosnia, Serbia, Bulgaria, Rumania ) – Geographicus, Daniel de Lafeuille, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

1738 Ratelband Map of the Balkans ( Bosnia, Serbia, Bulgaria, Rumania ) – Geographicus, Daniel de Lafeuille, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

August Zeune, who named the peninsula, consistently held to his conviction in 1808: “The Balkan Peninsula is separated from the rest of Europe in the north by the long mountain range of the Balkan Mountains, or the former Albanus, Skradus, Hemus, which adjoins the Alps in the northwest via of the small Istrian peninsula, while towards the east it disappears into the Black Sea in two branches.”

Although the name Balkan was increasingly entering the vocabulary of observers and commentators, few of them knew its exact meaning. The word Balkan is associated with a mountain: in most Ottoman and Turkish dictionaries it has the meaning of a mountain or a mountain range, in some it is defined as a wooded mountain, and in others as a passage through densely wooded Rocky Mountains; the word balkanlik also means a densely forested and rugged zone. According to Halil Inalcik, the Ottoman Turks first used the word Balkan in Rumelia in its general meaning of mountain, using additional names or to define it geographically. Thus, the word Emine-Balkan denoted the easternmost slopes of the Balkan Range that descend towards the Black Sea. The combination Emine-Balkan is a literal Ottoman translation of the word “Hemus-Mountain”: from the Byzantine “Aimos”, “Emmon” and “Emmona” the Ottoman Turks also derived the word “Emine”.

In the middle of the 19th century, many authors began to apply the name Balkan to the entire peninsula without any desire to challenge the primacy of earlier names that reminded of its ancient or medieval past: “Hellenic”, “Illyrian”, “Dardan”; “Roman”, “Byzantine”, “Thracian”. Until the Congress of Berlin in 1878, the most common designations referred to the presence of the Ottoman Empire on the peninsula: “European Turkey”, “Turkey in Europe”, “European Ottoman Empire”, “European Levant”; “Oriental Peninsula”. Ethical labels were increasingly used: “Greek peninsula”, “Slovenian-Greek peninsula”, “South Slavic peninsula”. And within that region itself, the “Balkans” was not the most common geographical self-determination. For the Ottoman rulers it was “Rum-eli”, literally “the land of the Romans”, i.e. the land of the Greeks, “Rumeli-i-sahane” (Imperial Rumelia), “Avrupa-i-Osmani” (Ottoman Europe).

by Omer Merzić, MA

Dobra knjiga