Presentation

Language and Identity in the Balkans. Serbo-Croatian and its Disintegration is an book by Robert D. Greenberg, published in 2004 by Oxford University Press. Robert D. Greenberg is an academic specialised in Slavic Studies. This book is the result of several years’ fieldworks and readings. The 190 pages (170 excluding the bibliography) of this work deal with Serbo-Croatian from its conception in the 19th century until the 4 languages that succeeded it after 1992 and their development up to 2004/2006: Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian.

The author begins by looking at the history of the codification of a language common to Serbs and Croats despite their many dialects. He then looks at its existence, which has been punctuated by controversies. Finally, he looks at the codification after 1992 (when the collapse of socialist Yugoslavia began) of Croatian, Serbian and Bosnian, and the beginnings of Montenegrin. He organises his work into 7 parts (including an introduction and a conclusion), each divided into (sub-)sub-sections. Here they are summarised below with key points:

I – Introduction

Robert D. Greenberg begins his paper by presenting his inspiration, aim and method. The many works from different academic disciplines on the subject of Serbo-Croatian, its disintegration and the cultural and political issues of its successors often take sides. This is for this reason that he wants to publish a book that is not Serb-centric nor Croat-centric.

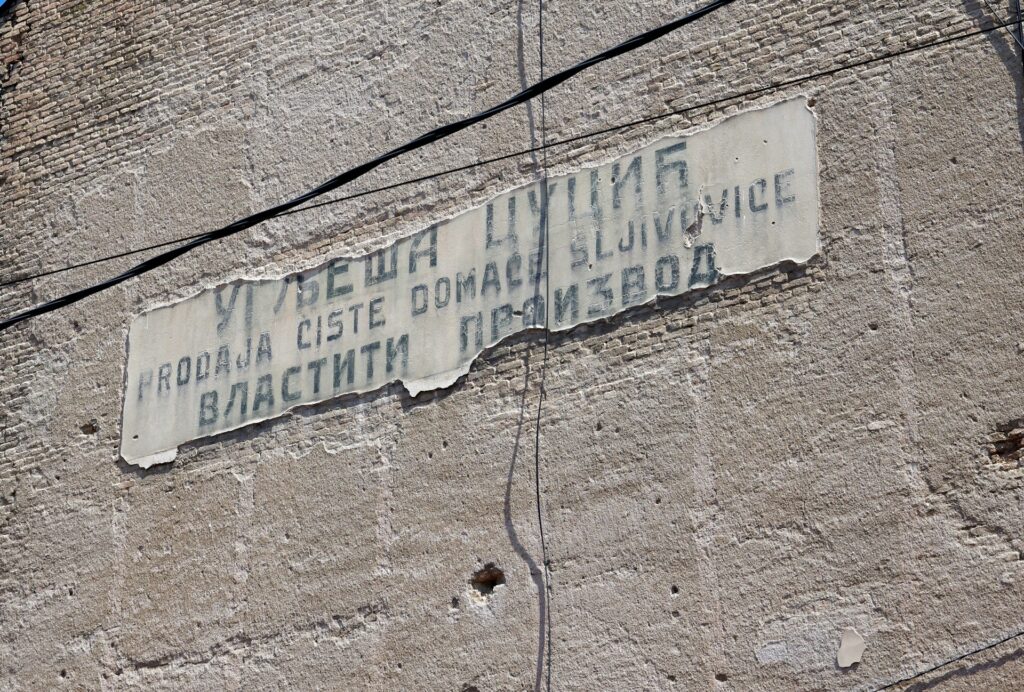

He reminds us that in the 19th century, the romanticism, nationalism and independences achieved (or proclaimed) were to a very large extent led through language. Language proved to be a powerful symbol of identity, and this also affected the Balkans.

Finally, using maps and clear explanations, the author explains the different dialects, pronunciations, similarities and combinations of Serbo-Croatian and the languages of the territories of the future South Slavic states.

II – Serbo-Croatian: United or not, we fall

This section provides an overview of the birth of Serbo-Croatian through 19th century. The author describes the literary and linguistic initiatives at the beginning of that century that later led to the codification of the language. The aim was to unify the peoples of the same region, despite their differences. This linguistic union was part of and also a starting point for a political union that would be realised through the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, just after the First World War.

The author also presents Vuk Karadžić and Ljudevit Gaj, their grammar books and dictionaries and their efforts, challenges and choices that led to the codification of future Serbo-Croatian. It also details the three models of linguistic unity: centrally monitored unity, government-imposed unity, pluricentric unity. Serbo-Croatian went through the three of them in that order and followed the pluricentric unity model during socialist Yugoslavia (1944-1992).

Finally, he quotes the linguist Bugarski, who defines Serbo-Croatian as having a weak internal identity within Yugoslavia. On the other hand, beyond the borders, this identity is strong and often claimed, because it shows the union of the different peoples and constituents of this State. This weakness can also be seen through the many controversies, tensions, the opposition and resistance that the language and its implementation have provoked, even before the socialist era.

III – Serbian: Isn’t my language yours too?

This third section only deals with Serbian, i.e. the standard Serbian that replaced Serbo-Croatian from 1992 onwards in Serbia, and in Montenegro from 1992 to 2004. Robert D. Greenberg presents the two variants in use in these territories, and the beginnings of a voluntary distinction for a future Montenegrin.

Once again, in both Serbia and Montenegro, debates between fractions of linguists, oppositions and controversies are numerous. They all are proof of the cultural, social, identity and political conflicts that contributed to the total disintegration of socialist Yugoslavia. One of the reasons for this is that Serbian speakers speak different variants and live in (at least) 3 different states: Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Serbian standard language is based on two dialects and two pronunciations and therefore it is more diverse as a standard language than standard Bosnian and Croatian.

The author goes on to discuss the importance of institutions and academies in codifying and sanctioning the language. Writing, lexicon, orthography, pronunciation, religious and ethnic implications, among others, are examples of the responsibilities and guidelines of these Academies.

IV – Montenegro: A mountain out of a molehill?

In this fourth part, Robert D. Greenberg looks at Montenegrin and its slower development. Indeed, the ideas and desires to establish a standard Montenegrin language distinct from the others (Serbian and Croatian) do not date from the 1990s. Awareness of a different literature and language goes back much further in time. However, these ideas and desires were reinforced at a rather later moment, especially following the Croatian protest movements and demands, more precisely since the 1970s.

At the start of the disintegration of Yugoslavia and just before independence in 2006, the demands were more and more vivid. Debates, controversies and oppositions followed. This book is published in 2004, therefore the author evokes the future of a Montenegrin language distinct from Serbian that is not official yet. The birth of a language concretised after the referendum on independence scheduled for 2006. I must add that in 2007, the proclaimed independence and the Constitution marked the beginning of the existence of a Montenegrin language with its own characteristics (pronunciation, lexicon, alphabetical characters). Here again, language is very closely linked to identity.

Here too the author discusses the many difficulties involved in establishing and codifying this successor language of Serbo-Croat and distinct of Serbian. Which dialect(s) should be chosen? What should be done with a (large) part of the population claiming to be Serbian and speaking Serbian? The author concludes this section by asserting that the existence of Montenegrin as a distinct language is the final step in the dissolution of Serbo-Croatian.

V – Croatian: We are separate but equal twins

In this section focusing on the Croatian language, Robert D. Greenberg looks back to the 19th century and then at the specific characteristics of the Croatian language, which does everything it can to differentiate itself from Serbian. This desire to be different (because it is impossible to fundamentally opposed them) does not date from the 1990s. Croats have always claimed their own history, identity, language and dialects. The author looks back at these claims, these differences, these debates and these struggles for the recognition and establishment of a language distinct from Serbian, since the mid-nineteenth century, despite the standardisation of Serbo-Croatian.

This section therefore looks back at the genesis of this unified language bearing a unifying objective but from the Croatian point of view. It also shows the codification of Croatian from 1992 onwards. This is an interesting aspect because we can see the often expressed desire to clearly distinguish Croatian from Serbian and the Serbs, accused of being imperialist. This rejection is not the first in their relations since in the previous century efforts were made to counter the magyarisation and germanisation of Croatian society and language.

To this end, after socialist Yugoslavia, the Croatian language was purified of “serbisms” and “internationalisms”, partly by removing Serbian terms and creating new words based on “uniquely” Croatian characteristics, or using again forgotten words in modern Croatian. Everyday attitudes are also one of the manifestations of this rejection, since speakers of Serbian or users of words considered to be “Serbian” are seen in a bad way. This mainly concerns the lexicon since the grammars are almost identical. Despite this, debates, controversies and hesitations mark this process as much as other successors of Serbo-Croatian.

VI – Bosnian: A camel with three humps?

This last part concerns Bosnian and “Bosniac”. These two terms misused or serving identity goals show all the complexity of the linguistic question in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

In Bosnia-Herzegovina live Serbs, most of whom live in the Serbian entity Republika Srpska, and Croats, most of whom live in the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The country’s third constituent group and also the majority are the Bosniacs. This term refers to Muslim Bosnians, as being distinct from Orthodox Serbs and Catholic Croats. In theory, all of them are Bosnians since they all are citizens of Bosnia-Herzegovina (and not all of them have a faith or practice it). In reality, since the war, the three have become more and more separated.

While the term “Bosniac” refers specifically to Muslim Bosnians (sometimes more generally to Muslim Slav), the term “Bosnian” can refer to the citizens of Bosnia-Herzegovina no matter their religion, and to the language of the country.

Serbs and Croats in Bosnia-Herzegovina have languages and kin-states some tend to identify with: Serbia and Croatia. On the other hand, Bosniacs are attached to the term “bosanski”, “Bosnian”, for the language spoken by them and in the country in general because they feel attached to the region and this more global term. Bosnian Serbs can say they speak Serbian or Bosnian, and Bosnian Croats can say they speak Croatian or Bosnian. It usually depends on the identity, cultural, political implications the name of the language(s) bear.

Some nationalists such as Serbs accuse Bosniacs of using the term “Bosnian” to deny the existence of Croats et Serbs in Bosnia-Herzegovina. But those nationalists also call the language “Bosniac” while they deny at the same time a language distinct from Serbian for Bosniacs. At the end of the day, the language is Bosnian and each one uses the name they want to use.

Nonetheless, with time and the work of the Bosnian language’s codifiers since the 1990’s, Bosnian language tends to use more and more “Bosniac” elements. Understand: elements used especially by Bosniac and more linked to Muslim culture, as distinct form Serbian and Croatian. It means for example words borrowed from Ottoman Turkish and some pronunciation such as the use of the letter and sound “h”. Here once again we see that language is a strong marker of identity.

VII – Conclusions

This concluding section is much appreciated, as it sums up the most important points made throughout the book.

The 19th century saw the codification of a unified language bearing a unifying purpose: Serbo-Croatian, or Croatian-Serbian, the language of the South Slavs who were united in 3 several states from 1918 to 1991 (and 2003 for Montenegro).

As time went on each constituent republic and then state claimed its own uniqueness and distinction from its neighbours. This led in part to the disintegration of Yugoslavia and Serbo-Croatian.

This language has 4 standard languages successors: Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian and Montenegrin. Since language is a symbol and marker of identity it is easy to understand why it is at the heart of cultural and political demands. It is also understandable that it has provoked many long-lasting debates, controversies and oppositions. The name in itself of these languages is a delicate issue.

Every people and every state wants (or would like) its own language, different from those of its neighbours. And the process in 2004 is not yet complete since Montenegrin is not yet official and Bosnian is still evolving.

Concluding remarks and recommendations

If you are interested in Serbo-Croatian or its successor languages, then Language and Identity in the Balkans. Serbo-Croatian and its Disintegration is for you. In just a few pages given the density of the subject, Robert D. Greenberg succeeded in summarising and presenting clearly the evolution, the issues and the complexity of linguistic and political questions in former Yugoslavia.

The book is divided into sections of 2 to 5 pages making it very accessible whether you want to find out more about it, expand your knowledge or deepen it. Content is organised and this helps us to see things even more clearly and to grasp and assimilate the information more easily. What’s more, the maps, quotes, language extracts, tables and chronological timelines make it even easier to understand. Finally, the many names cited (of linguists, for example) help to broaden horizons by providing references to check.

This book provides an insight into the linguistic, social, cultural and political aspects of Serbo-Croatian, Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian and Montenegrin.

If you are interested in “naški”, “our language”, language and identity: read it.