Author: Vladimir Petrović

I know this title sounds just like a grumpy lament, but it is not. It is an honest warning. To the best of my knowledge, all countries vanish. I know it is a difficult pill to swallow. Homo sapiens is good in many things, but dealing with finality is not our forte. Not many people think of their own death. Why bother? We all know we will die, so rubbing it in makes little sense and could actually be detrimental to whatever time we have left on this planet. We take solaces instead. Some turn to hedonism, some are convinced in afterlife. Others hope that they will leave something behind, that their families will outlive them, perhaps even cherish their memory. But whoever visited a graveyard knows that this is rarely the case. Most families disintegrate after a couple of generations, all tombstones fall into disrepair sooner or later – even the pyramids. Just remember the 1819 Ozymandias sonnet of Percy Shelley. In that respect, not much has changed. We will leave behind more or less embellished social network profiles, covered with a handful of obituaries. They will trickle and sooner or later fall into a digital dust.

Percy Shelley, Ozymandias

If you are still with me, dear reader (and I don’t blame you if you are not), I would like to direct your attention toward a simple fact – this applies not only to individuals and families, but to entire groups of people, even collectives such as nations. Also, no matter how different we think nations are, I can assure you that late 19th century French peasant had more similarities with his Serbian contemporary then with a 21st century Frenchmen. No matter how inclined we are to think that nations are set in stone, they are actually in perpetual motion, reinviting themselves as they encounter historical and technological challenges. Those who manage, like Japanese, persist. Those who do not, fall into oblivion, like Ainu people whom they colonized.

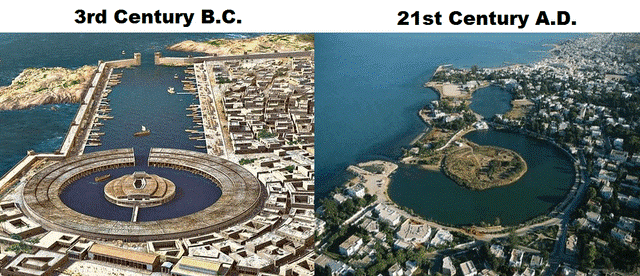

That instability applies to other human ventures too, from buildings and institutions to entire countries and even civilizations. Our elders had no doubts about that, as any reader of Polybius would know. Looking at the ruins of once might Carthage, side by side with Roman general Scipio who obliterated it so successfully that I had serious problems finding it in contemporary Tunis, he came up with his Histories. They indicate the inevitability of rise and fall of all empires. He would probably not be surprised to hear that half a millennia later the same happened, not only to the Roman settlement which was built on the ruins of Carthage, but to Rome itself. Once might empire is reduced to a tourist destination.

Est ubi gloria nunc Babylonia?, asks late medieval poet: “Where is now your glory, Babylon, where is now the terrible Nebuchadnezzar, and strong Darius and the famous Cyrus? Where is now Regulus, or where Romulus, or where Remus? The rose of yore is but a name, mere names are left to us.” This last sentence inspired Umberto Eco’s famous novel The Name of the Rose.

You might choose to believe that those are some bygones, that temporary empires are more resilient, but nothing would be further from truth. Hitler’s “Thousand-year Reich” (fortunately) lasted only for twelve years, however producing an unparalleled catastrophe during its swift rise and fall. As everything speeds ups, so do the processes of spasmodic social change, of which we can read in Paul Kennedy’s The Rise and the Fall of Great Powers. Progress, which is actually our true secular religion is not assured at all as we are reminded by Ronald Wright’s short, but disturbing book on the issue. If anything, our civilization is more vulnerable than its predecessors, due to the interconnected nature of contemporary world. Certainly, not all is lost. Even after collapse, what remains is a memory, but we all know how selective that can be, also distorted to serve the interests of the present and mostly geared to disable us to understand those simple truths.

How do I know all that? Being a child of Enlightenment, disappointed but still a child, I wish I could say that I learned it from books, but the actual realization mostly came from experience. My grandmother Nada (the Hope) was born in 1912. She was a subject of the Ottoman Empire, Kingdom of Serbia, Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, Yugoslav kingdom, German occupied territory of Serbia, Democratic Federal Yugoslavia, Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Parting in 1997, she outlived them all. Had she lived a couple of years more, she would also see, as I did, not only the collapse of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, but also dissolution of and creation of Republic of Serbia. And all that without moving at all.

You might say, well Vlado, nothing against you and your granny, but these are just your experiences. Are you not from the Balkans? We feel for you, but what gives you the basis for those fearmongering generalizations? I wish you were right, and I admit I am prone to that but I am doing neither. Indeed, I am from the Balkans – borders there do change a lot. Actually, as of recent, according to the EU lingo, I am from Western Balkans However, I travelled extensively enough to notice an interesting regularity – whenever there is a coinage which mixes side of the world with politics, it is an unmistakable sign of troubles. Just think – Northern Cyprus, but also Northern Ireland. South Ossetia and Soth Sudan, West Bank and Western Sahara and East Timor. All regions of troubled past and uncertain future.

But let’s not exoticize too much, my European friends. There also was Eastern Germany, also known as Democratic German Republic? Where is it now? Gone, annexed by Federal Republic of Germany, which retained the name but has changed completely in the process. It not only enlarged but also gave a lot of its sovereignty to European Union which over my lifetime I saw transformed from European Community, growing larger and deeper, and then territorially shrinking and structurally loosening. However, it is still in some kind of shape, especially compared to other unions I saw, such as Soviet Union, which vanished very quickly in 1991 despite the opening words of its mighty anthem which celebrated the Unbreakable Union of freeborn Republics. Its Cold War antagonist, the United States of America, emerged triumphant from this confrontation, but has soon ventured into an imperial overreach, squandering its unipolar momentum and entering its own structural crisis, announced already in 2000 by Morris Berman’s Twilight of American Culture.

So, trust me, countries vanish. And this is not to spread fear, not even to sound the alarm, but rather to call for action. For they don’t vanish in the same way. Some crumble in chaos and warfare, like Yugoslavia. Some disintegrate seemingly less violently, like the USSR. But gates of hell recently opened by Putin’s Russia show that even disintegrations are not necessarily irreversible, as its deadly grasp hangs over Ukraine. Some vanish completely, like DDR, others retain the brand, like Federal Republic of Germany, but change completely, perhaps even for the better. Others, like Syria, might keep the name, but deteriorate completely from within, resembling a huge prison. Some vanish into dust, like Hitler’s Germany and imperial Japan. Others lose global supremacy and overseas possessions, wreaking havoc from India through Palestine to Cyprus, but still call themselves United Kingdom. Some dismantle their empires more discreetly, like the Netherlands, opting to focus on making profit silently. Others maintain that influence indirectly, concealing an empire under a humble name of United States of America. Yet they are all in perpetual motion, competing with each other, even progressing but actually inevitably decaying somewhere down the line.

Therefore, the key question is not if an entity which we call a country, to which we feel attached to, which gives us a sense of stability and pervades our identity so much so that sometimes we are even ready to die for will disappear. It will. The question is when and how. Namely, the disappearance of the state is not necessarily a tragedy at all. After all, Nietzsche who was wrong about so many things called the state “the coldest of all cold monsters. Coldly lieth it also; and this lie creepeth from its mouth: I, the state, am the people.” And indeed, we are told that the people created the state, as a kind of a social contract, to protect themselves and create conditions to live fruitful lives in relative freedom and safety. Sometimes that is actually the case. But the horror occurs when a state starts squandering the resources of generations, turns against its own citizens and starts engulfing them, destroying physical lives in tens of thousands and damaging wellbeing of millions.

That is what occurred in Yugoslavia. As I have spent most of my professional life staring at that abys, I am offering some insights of my colleagues from Institute of Contemporary History Innovation Center of in modest hope that they might help averting agonies on much larger scale. Back in the days, while chaos was engulfing my country, the West was lulled in a Fukuyamian end of history pipedream. Many were relying on dubious theories such as Golden Arch Peace, basically asserting that there will never be war between countries which have MacDonalds. Conflict situations in the Balkans, Caucuses, Central Africa were discarded as historical incidents, international courts were set in motion to address them as the rest of the world seemed to move on to posthistory, cable television entertainment, rave parties and internet.

It took a shock of September 11 to announce that history is back, with all its darker sides. War is back. Diseases are back. So are the famines. Actually, none of those ever left our planet, but they were concealed from the Western eye, contained in the global south. It took global economic crisis, climate change, mass migrations and war in Europe to let the message sink in. Deep down, we all know that the clock is ticking on us. However, such prospect is so harsh that too many people simply refuse to admit it. Why is that the case? Firstly, it is about comfort. Such realization would call for action, and that action would have to include a radical change of lifestyle. That would include deprivations, which could sound outlandish – imagine if somebody ordained that flights should be reduced to essential travels, for example, or half a day of mandatory unpaid public work on Saturdays. There would probably be riots. People are happier to reduce their “suffering” to recycling and occasional donations. But deep down we know that will not do. If we don’t make use of that knowledge, and fast, posterity will judge us harshly, but rightfully as a bunch of people who could get informed about everything but to no avail.